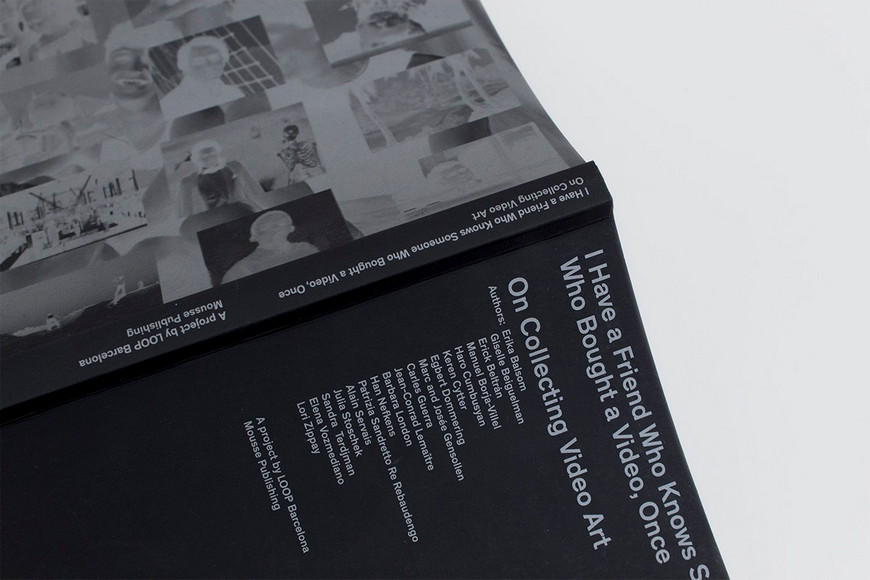

Mousse Publishing, 2016

160 pages. Softcover, 15,5 x 21 cm. ISBN 9788867492190

Edited by LOOP Barcelona. Texts by Erika Balsom, Giselle Beiguelman, Erick Beltrán, Manuel Borja-Villel, Haro Cumbusyan, Keren Cytter, Egbert Dommering, Marc and Josée Gensollen, Carles Guerra, Jean-Conrad Lemaître, Barbara London, Han Nefkens, Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Alain Servais, Julia Stoschek, Sandra Terdjman, Elena Vozmediano and Lori Zippay

“Video Art’s Secondary Market” by Elena Vozmediano

Video art is fully established in the primary market. Its presence in galleries and fairs is abundant, while at the same time it features prominently in institutional exhibitions, collections, and museums. Video ceased to be a “new medium” a long time ago; its artistic use, in fact, dates back half a century. Yet up until today, the secondary market has been very reluctant to integrate it. Why? Every time this question is asked, the answers given have to do with technological obsolescence, the distrust regarding editions, the added conservation difficulties for these formats, the fact that the pieces cannot be permanently exhibited, and the related exhibition rights. All of this is true, but it does not account for the notable difference in reception between the primary market, where video art is somewhat of a success, and the secondary, where it hardly exists. Let us broaden our perspective a little bit.

First, we need to take into account that, although several galleries in Europe and the United States started to put out limited video art editions around the late 1960s, [1] these editions generally had large print runs, and the recordings and copies were of a quality that we nowadays consider poor: both of these factors made them in- appropriate for auctions. The first commercial exhibitions by artists such as Bill Viola, Dara Birnbaum, and Gary Hill took place during the early 1990s, already with different technical conditions and commercial strategies. [2] This delay led private collectors, who provide the secondary market with works, not to integrate video art in a stable manner until relatively recently. [3] And given that video does not easily lend itself to speculation (because of the evolution in its prices), the works acquired by collectors have mainly remained in these original collections. Although the first auction of an artwork with an audiovisual component took place in 1988—I am here thinking of Nam June Paik’s video sculpture Family of Robot: High Tech Child (1987)—it was much later that artists’ films and videos entered the secondary market. It was not until 1999 and 2002 that William Kentridge and Bill Viola, respectively, sold a piece at auction. It is then clear how the business scenario we are describing is still taking form and has little more than a decade of history.

It is also a scenario without well-defined borders. Videos have more than one marketing channel, something that makes them differ from media such as painting, where unique objects are produced. Since very early on, artists allied themselves with organizations that, seeing the market’s weakness in audiovisual art and the need to introduce this little-known field to the public, came up with another model to make these works profitable by selling them in editions (often unlimited), renting them, and, later on, making them available for online viewing. [4] This alternative path, which has had multiple beneficial effects for artists, has taken weight off the traditional sale channels centered around galleries, where regular contemporary art collectors go. And this is not the only “deviation” that audiovisual art production has taken: indeed it has also plunged into the experimental cinema scene, where it gets promoted and marketed by specialized festivals.

In order to explain the aforementioned delay, we ought to consider as well that many museums have lacked an audiovisual collection or department for decades, and that those who did own pieces or were interested in the medium approached it, especially up until the mid-1990s, via screenings and media libraries, with a much smaller public impact than exhibitions. These museums therefore gave the impression that video art was a discipline for “the initiated” and for specialists, oriented to a great extent toward research. Later on would come the time for video installations and plasma screens, which took video into the exhibition space. There is a close correspondence between what the museum values (and how it values it) and what the market demands. Video art buyers were, for some time and to a certain degree, specialists who fit neither the typology of the impulsive and capricious collector nor that of the investor who expects to make economic profit. Instead, the typical video art buyer had made an effort to learn about a lesser-known chapter in recent art history while acquiring the necessary technological background. It is quite likely that some of them consider their collections more of a personal than a monetary investment, one they would not let go of easily. Furthermore, up until recently the prices of video works were not outlandish, given the difficulty of selling or reselling them. This makes it quite likely for a collector who is not undergoing any serious economic hardship not to see much sense in putting out into the market a piece that wasn’t very costly and for which there is no assurance of profit.

Other aspects of video art’s primary market contribute to the absence of a secondary market. Over the last few years of the recession in Europe, some corporate collections have been dismantled, either because of a company’s collapse or due to the need for liquid assets. It is common to see the works in these collections arrive at auction houses, where they offer greater profitability. But it is rare to see companies, corporate foundations, or banks pay attention to video art. It makes sense: the company tends to consider art an investment and thus privileges the object with a physical presence and a more or less safe market value. Several collections of this sort have centered around photography, but I have no knowledge, at least in Spain, of one dedicated exclusively to video art. It is quite telling that even though the Fundación BBVA has launched generous grants for video art creation, the bank does not own a single piece of the kind in its well-nurtured collection.

The uncertainties surrounding video art grow larger due to a matter that may seem unimportant but in fact isn’t: the fiscal aspects. Remember the famous European Commission sentence on the import taxes that needed to be paid for some of Bill Viola’s and Dan Flavin’s pieces that Haunch of Venison gallery introduced in 2006 in London? In 2008 a British court had informed customs officers that the electric and electronic material that was part of these artists’ installations ought to be taxed as art, with a reduced 5 percent VAT, and not as “DVD players and projectors” or “light accessories,” which would be taxed at 20 percent. But the European Commission argued that “the artistic nature of these pieces rests not on the material elements intervened, but instead results from their ulterior assembly and disposition.” [5] Obviously it is necessary to better define and regulate many aspects related to international trade in order to provide stability for these operations.

To this day, the large auction houses lack video art departments. Video art is hardly mentioned by some of the most widespread studies on the art market. As Noah Horowitz points out: “Art market economists continue to focus almost exclusively on painting in their analyses of art’s investment value, as a number of important recent books on the art economy, such as those by Don Thompson and Clare McAndrew, have ignored video art altogether.” [6] As a consequence, investors do not trust a medium that market studies pay no attention to. For instance the 2015 Contemporary Art Market Report released by Artprice does not include a single sentence about video art. Neither does the 2014 or 2015 Art Market Report by TEFAF.

None of the large auction houses have ever organized a sale focused exclusively on video art, whose presence in the secondary market remains minimal, with total sums amounting to less than 1 percent of the global contemporary art market. [7] In September 2013 in New York, Christie’s organized “First Open: New Media,” where they showcased different types of works not frequently seen at typical contemporary art auctions. Only four pieces, however, contained moving images. Most were photographs (new media?). The highest bid, $60,000, which fell within the estimated price range, went for a piece by Jennifer Steinkamp.

Outside art market capitals, video art resale has barely taken off. In Melbourne, Australia, Sotheby’s led the way in 2007 by auctioning Shaun Gladwell’s Storm Sequence (2000) for Australian $84,000, a sum that remains the highest among sales for that country, where according to the January 2014 Australian Art Sales Digest total video resales in the last five years amount to only Australian $72,000. In 2013 Heffel auctioned in Canada the first video art piece, by Judy Radul, which was sold for Canadian $2,925, half its initial estimate. In Spain, after Odaly’s first initiative in February 2009, when two pieces by the French artist Pascal Loubet and the Venezuelan Alexander Apóstol were resold, we only had the almost incidental partnership between MADATAC (International Festival of Contemporary Audiovisual and New-Media Art Technologies) and Casa Segre, who put up for sale the winning works of a prize organized by the festival between 2009 and 2014. In the first edition, the auction clearing prices oscillated between €500 and €1,600 (for The Kiss [2006] by the British artists Kye Wilson, Denise Callender, and Neil Hunt). In this last edition, out of three pieces, only one was sold: a piece by the Chinese artist Liu Yanhu, for €500.

Currently the only auction dedicated exclusively to this medium is #ARTVIDEO, organized by Vincent Wapler house in Paris in January 2014, with discouraging results. From a catalog of 159 pieces, 48 were sold, for a total sum of €46,680. In March 2015 this same house gave it another try but modified its strategy, adding a good number of other media works to the catalog: 350 lots in total, out of which 89 were audiovisual. Twenty were sold, with a top price of €7,000 for a piece by Charles Sandison. [8]

It is clear that, in general, the art market prefers objects. And this feature is reinforced in the secondary market, where prices are often higher and where collectors are perhaps more cautious about “risks.” It is not surprising that the most successful video art pieces at auctions are those that incorporate some objectual or sculptural element. The “video object” has in itself no interest for the collector: a VHS tape, a laserdisc, a DVD—as much as they get presented in carefully designed boxes, they nonetheless remain mere recording platforms with no artistic value. Photography, another editable medium, has a much stronger objectual status, especially in the case of vintage or large-format prints, and therefore is far ahead of video in terms of sales and prices, in both the primary and the secondary market. In addition to that, digital video is nowadays an affordable and easy-to-use technology. This has not only fostered its growth in popularity among artists (where there is an overabundance of audiovisual production), but has also introduced video into our lives as a tool for leisure (or work, or whatever use). These circumstances have a lot to do with the formal evolution of video at the turn of the century and with its artistic status. On the one hand, we find that the market and museums (when it comes to display) tend to prefer video installations and video sculptures, which provide the image with a materiality that triggers a “holistic experience.” On the other hand we are fascinated by cinema’s huge blockbuster productions, with their incredibly expensive professional equipment and mind-blowing image quality that mark a distinction from amateur video. Both trends lead to an increase in prices that the market considers beneficial to the upturn of the value of the medium. Or is it maybe the need to increase prices in order to increase the artists’ recognition that leads to the use of these formats and production models?

But it is very hard for more complex and sizable video installations to reach auctions. Even when an auction is organized around large-format installations and sculptures—such as Thinking Big in 2013, where Christie’s put up for sale works from the Saatchi collection—the audiovisual component is left aside. [9] To assemble their video installations, artists require a certain architectural setting, certain acoustic conditions, a heavy “scenification” conceived for museums, which only important private collections with large exhibition spaces can host. [10]

The single-channel video, since its early commercialization in galleries and its inclusion in exhibitions, calls for a large-format projection in order to gain physical presence, but it also shows a desire to be objectual: certain pieces are presented in old, squared professional monitors that are nowadays so valuable (and so hard to repair and replace), or, in the case of recent works, on luxurious high-definition screens that emulate the “pictorial format.” [11] Because they are easily integrated into exhibitions and simple to use, these screens work much better in the field of private collecting.

Following this preference for a physical presence, auction houses, as Erika Balsom points out, have paid more attention to secondary products than to the videos themselves. Photographs, whether they are video stills or independent works produced in parallel to filming, as well as the objects used in the scenography (or the clothing), have a higher demand, as astute artists and galleries know. Matthew Barney’s case is often mentioned, because he delivers a whole set of objects and photographs with each of his Cremaster installments. The highest prices reached at auctions tend to correspond to these “mixed” pieces that are both audiovisual and sculptural. In Barney’s case, a Cremaster 2 “kit” was sold for US $571,000 in 2007.

Art market analysts, as we have already mentioned, do not bother to closely follow the evolution of video art pieces in the secondary market. It is only every so often that a small, partial report is published. They always refer to the few renowned figures that occupy the first places at auctions, but they leave aside some significant facts. For instance, Bill Viola’s last four pieces that Sotheby’s presented at auction in June 2014 found no buyer. Among those pieces is the same copy of Eternal Return that made the artist reach his £377,600 record in 2006, even when he was not aiming for a large profit, given that eight years later the piece was auctioned with an estimated price of £300,000 to £400,000. Yes, those prices are very high, but according to Artprice, a total of sixty-seven pieces by Viola have been auctioned, only thirty-seven of which were audiovisual (very few, really).

Let us further analyze the artists who are most valued by the market. For William Kentridge, Artprice provides us with 993 auction results, but only thirteen were audiovisual pieces! The most expensive one, from 2011, was Preparing the Flute(2005) (US $602,500), a miniature theater that included two films, although Kentridge’s absolute record is for a sculptural installation, Procession (1999) was bought for US $1,538,500 in 2013. Nam June Paik has had sixty-eight pieces with audiovisual components auctioned (a total of 795 in all media), reaching his top price with TV Is Kitsch (1996), which sold for Hong Kong $4,220,000 (€496,413) in 2011. Bruce Nauman has had fifty-two video pieces auctioned, the most expensive of them being Coffee Spilled and Balloon Dog (1993) (US $485,000 in 2013). With more moderate prices, Tony Oursler has auctioned fifty-five.

It is surprising to see such revered artists as Gary Hill sell so little in the secondary market (six audiovisual pieces, twelve in total), with records comparatively humble—in Hill’s case US $169,000. Not a single video by Joan Jonas, Martha Rosler, or Wolf Vostell has been auctioned. None by Harun Farocki. None by Antoni Muntadas. By the very famous Marina Abramovi?, only one video, Stromboli I(2002), was auctioned in 2009 for just €20,000.

Some Asian artists working with video have reached very high prices, but the dynamics are not all that different. After All I Didn’t Force You, a video by Yang Fudong, was sold in 2014 for Hong Kong $687,500 (€80,765), although his most expensive piece is a photograph that sold that same year for Hong Kong $1,480,000. Only two audiovisual pieces by him have been auctioned. Some of the best-paid video artists do not work exclusively with this medium: they produce other kinds of works, generally even more expensive. Such is the case for Qiu Zhijie, whose performance Writing the Orchid Pavilion Preface One Thousand Times (materialized in the form of a video, a drawing, and seven photographs) sold in 2011 for Hong Kong $1,820,000 (€214,093).

On a lower price range are other video art stars with occasional presence at auctions. By Doug Aitken, for instance, 126 pieces have been offered, but only five of them were audiovisual (the most expensive one being a video installation with five screens, I am in you, sold for US $176,500, in 2010). By Pipilotti Rist, twenty-one videos (from a total of 132 works), with a £8,075 record for a sculpture that included three small video projections, Bar (1999). By Douglas Gordon, eighteen (out of 219), with a £46,850 record, also for a piece with a strong sculptural component, Site Specific Predictable Incident in Unfamiliar Surroundings (1995). Shirin Neshat has joined video art top figures by selling Passage (2001) in Doha, in 2014, for US $269,000. We should bear in mind, however, that out of her 615 pieces auctioned to date, only two have been videos. By David Claerbout, The Algier’s Section of a Happy Moment (2008) sold for a high price (£120,100), although his other audiovisual pieces were auctioned for less than £25,000.

If we take a look at younger yet very famous artists, we find that appearances are very scarce. By Anri Sala, twenty-six pieces have been offered, with just one video sold for £20,000. By Christian Marclay, three (out of 106). By Julian Rosefeldt, two. By Isaac Julien and Tacita Dean, none!

But does video art’s weakness on the secondary market harm anyone? I dare to say that it does not harm the artists, as we have seen that some of the most acclaimed, who work with powerful galleries and participate in important exhibitions and biennials, have not entered the auction scene. It is true that when an artwork is resold, a percentage of that operation (which can amount to a considerable sum) goes to the artist, but it is also true that many artists, whether they work with video or with other media, try to avoid the auctioning of their pieces for fear of losing sight of them or, especially, for fear that they will not reach the prices they were sold for initially (and galleries often support this choice). This “weakness,” then, does not harm those collectors who purchase audiovisual pieces out of sheer admiration or to support the artist’s career, since they have no intention to resell the works they acquire. The ones that are negatively impacted are collectors trying to make their art investment profitable.

That there is no demand in the secondary market could be a symptom that galleries are artificially inflating prices while leaning on, as it has been insinuated, production costs that are sometimes unnecessary and a limited-edition model that still seems unnatural for an endlessly reproducible medium. Leaving the most elitist market aside, the nature of social audiovisual consumption shows that the debate around the diffusion of and the marketing channels for video art remains open.

NOTES

[1] More details on this can be found in the article by Erika Balsom in this book.

[2] Noah Horowitz, Art of the Deal: Contemporary Art in a Global Financial Market(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), 92.

[3] According to the study “Collecting in the Digital Age. International Collectors Survey” carried out by Axa Art (2014, available online at axa-art.co.uk), only 14 percent of those surveyed collected installations and video art.

[4] The most active distributors have created the Dinamo network (dinamo-distributors.org).

[5] More information on this case can be found in the article “¿Hacia un concepto aduanero del arte?,” December 2010, http://www.legars.eu/?p=55.

[6] Noah Horowitz, Art of the Deal, 107.

[7] Ibid., 108. Horowitz explains the methodology for this calculation in footnote 88.

[8] The catalogs for both auctions, with final sale prices, can be checked at wapler-auction.fr.

[9] The auction, with fifty pieces, was held in London in October 2013. Twenty-three records were set on the occasion.

[10] However, some ambitious video productions will adopt several formats (from single-channel to multi- projection, according to the different spatial requirements) in order to adapt to market levels, and the most simple presentations should have easier access to the secondary market.

[11] Noah Horowitz, Art of the Deal, 122. “Growing use of wall-mounted plasma flat-screen televisions links up the third point concerning how present-day video art has come to occupy a reserve of sanctity and contemplation formerly dominated by painting. This reinforces comparisons between the video art and photography markets insofar as the large-scale dimensions and high-resolution finishes that have become characteristic of the latter have raised innumerable comparisons to the painterly tradition as well.”